What We Must Be Reconciled To and With

The section from which the passages that make up the Heart Sutra were extracted starts with:

Śāriputra asked the Buddha: in what way is a commendable one who aspires to fully awaken, and who is reconciling themselves to and with awakened understanding, to be called “reconciled”? The Buddha responded: Śāriputra, they are to be called “reconciled” if they are reconciled to and with the naturelessness of form and the other aspects of experience.

In the Heart Sutra, the text is ostensibly a one-way conversation between Avalokiteśvara, a bodhisattva or mythic being who has awoken, and the monk Śāriputra who was one of the most prominent disciples of the historical Buddha. Here we see that, in the Large Sutra, it is cast in terms of a (likely fictional) conversation between the Buddha and Śāriputra, both of which are (presumably) historical persons.

A bodhisattva can also mean one who aspires to become reconciled, and the term is generally used in the Large Sutra to refer to those who have not awoken, and/but who will not allow fear or confusion to sidetrack their efforts to fully awaken. I have therefore chosen "one who aspires to fully awaken" as a translation. One who has this aspiration is also called a "commendable one" (mahāsattva), a term often translated as “great being”, though when one starts out reconciling their beliefs to what is actually happening they are still like most everyone else (i.e., not yet great).

The initial focus of reconciliation is one of the ways in which Buddhist canonical literature suggests we can nominally divide up the content of our experience, that of the five aspects of experience (skandha): form, sensation, recognition, conditioning and consciousness. The term skandha is often translated as “heap” or “pile”, which may convey the sense that each is in some way separate from the other. As arbitrary categories, however, they are not actually separate, even if our analytical mind wants them to be.

A bodhisattva can also mean one who aspires to become reconciled, and the term is generally used in the Large Sutra to refer to those who have not awoken, and/but who will not allow fear or confusion to sidetrack their efforts to fully awaken. I have therefore chosen "one who aspires to fully awaken" as a translation. One who has this aspiration is also called a "commendable one" (mahāsattva), a term often translated as “great being”, though when one starts out reconciling their beliefs to what is actually happening they are still like most everyone else (i.e., not yet great).

The initial focus of reconciliation is one of the ways in which Buddhist canonical literature suggests we can nominally divide up the content of our experience, that of the five aspects of experience (skandha): form, sensation, recognition, conditioning and consciousness. The term skandha is often translated as “heap” or “pile”, which may convey the sense that each is in some way separate from the other. As arbitrary categories, however, they are not actually separate, even if our analytical mind wants them to be.

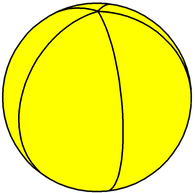

To emphasize they are not truly distinct, I suggest translating skandha as “aspect”, as if each is but one side of a five-paneled sphere as in the diagram to the right. None of the five aspects are necessarily more important than the other: it’s just that, depending on your perspective, one aspect may be more prominent than the other, as if the sphere rotates by which a particular aspect is now in front of you.

Dividing up what is happening into these five aspects is intended to comprise the entirety of our experience. Externally, we experience ourselves and all else as having or being a physical form, and internally we experience sensations, recognition, conditioning and consciousness. This isn’t the only way to parse what is happening in experience, and other ways follow in the next section. While the five aspects are not necessarily a perfect or exhaustive way of dividing experience, they are remarkably thorough, and are representative of what we experience about ourselves and the world around us.

Dividing up what is happening into these five aspects is intended to comprise the entirety of our experience. Externally, we experience ourselves and all else as having or being a physical form, and internally we experience sensations, recognition, conditioning and consciousness. This isn’t the only way to parse what is happening in experience, and other ways follow in the next section. While the five aspects are not necessarily a perfect or exhaustive way of dividing experience, they are remarkably thorough, and are representative of what we experience about ourselves and the world around us.

Part of the reason the five aspects can be a helpful way of approaching what is happening is our natural tendency to assume ownership of them, as if the five aspects describe “our” experience. In other words, we tend to see these five aspects as part of our very nature: we are, so it seems, by nature a physical and mental creature. However, if the five aspects are to be part of our nature, we need them to be real and substantial. If so, that allows us to believe that we too are real and substantial, and that the statement “I Am” is absolutely true. It can seem as though we couldn’t be having these types of experiences if there wasn’t an actual or substantial “me” in here somewhere. And yet, whether it is the five aspects or some other formulation, we don’t realize that they are natureless mental concepts.

Perhaps the most obvious of the five aspects is form, in that it’s something that not only we apparently have, but everyone and everything else seems to have it as well. We believe our body, and thus ourselves, to have an obvious and tangible physical presence in the world that takes up room in three-dimensional space, and we experience all else as having a physical and tangible presence also.

Form is therefore a very convincing aspect, and it may not occur to us that it is actually something we project onto whatever we experience. Because of this belief in “form”, it is natural for us to assume that all we experience is real and substantial, as if the screen on which you are presumably reading these words has a certain “screen-ness” nature associated with it that makes it what it is. Because “form” is so convincing and omnipresent, it’s no wonder that it is singled out as a focal point in the Heart Sutra.

Becoming reconciled to and with the fact that we don’t have “form”, as it appears we do, is not easy. After all, we likely cannot remember a time when it didn’t seem that way. We might tend to want to focus on provisional concepts such as “impermanence”, telling ourselves that we have an impermanent body rather than a permanent one, by which we might subtly hang on to our belief in it. Or, it might simply be too difficult or scary to imagine what it would be like to not feel like an embodied being. And yet, giving up our belief in this and all other aspects of experience is a natural part of awakening.

In the unfettering approach, the belief in “form” is completely cast aside when the 7th fetter “breaks”, which takes away our more fundamental belief that there a part of us, call it “perception” or a “thing detector”, by which we can perceive actual “somethings” with form in the first place. Along with that goes the belief that sensations, recognition and conditioning are actual “somethings” as well. Afterwards, breaking the 8th fetter results in letting go of the belief that there is something called “consciousness” that we not just have, but are. It is then the five aspects finally cease to be seen as anything but natureless concepts.

After that, many people experience a surprisingly amount and intensity of suffering. This is generally due to the fact that everything they have known, especially themselves, have been shown to be natureless mental creations. Working with the 9th and 10th fetters therefore involves examining the fundamental beliefs we have had throughout our lives regarding what it is we experience, and becoming reconciled to the fact that everything which happens in daily life is not as it has always appeared.

Perhaps the most obvious of the five aspects is form, in that it’s something that not only we apparently have, but everyone and everything else seems to have it as well. We believe our body, and thus ourselves, to have an obvious and tangible physical presence in the world that takes up room in three-dimensional space, and we experience all else as having a physical and tangible presence also.

Form is therefore a very convincing aspect, and it may not occur to us that it is actually something we project onto whatever we experience. Because of this belief in “form”, it is natural for us to assume that all we experience is real and substantial, as if the screen on which you are presumably reading these words has a certain “screen-ness” nature associated with it that makes it what it is. Because “form” is so convincing and omnipresent, it’s no wonder that it is singled out as a focal point in the Heart Sutra.

Becoming reconciled to and with the fact that we don’t have “form”, as it appears we do, is not easy. After all, we likely cannot remember a time when it didn’t seem that way. We might tend to want to focus on provisional concepts such as “impermanence”, telling ourselves that we have an impermanent body rather than a permanent one, by which we might subtly hang on to our belief in it. Or, it might simply be too difficult or scary to imagine what it would be like to not feel like an embodied being. And yet, giving up our belief in this and all other aspects of experience is a natural part of awakening.

In the unfettering approach, the belief in “form” is completely cast aside when the 7th fetter “breaks”, which takes away our more fundamental belief that there a part of us, call it “perception” or a “thing detector”, by which we can perceive actual “somethings” with form in the first place. Along with that goes the belief that sensations, recognition and conditioning are actual “somethings” as well. Afterwards, breaking the 8th fetter results in letting go of the belief that there is something called “consciousness” that we not just have, but are. It is then the five aspects finally cease to be seen as anything but natureless concepts.

After that, many people experience a surprisingly amount and intensity of suffering. This is generally due to the fact that everything they have known, especially themselves, have been shown to be natureless mental creations. Working with the 9th and 10th fetters therefore involves examining the fundamental beliefs we have had throughout our lives regarding what it is we experience, and becoming reconciled to the fact that everything which happens in daily life is not as it has always appeared.

They are to be called “reconciled” if they are reconciled to and with the naturelessness of the twelve sensory supports and the eighteen elements of experience. They are to be called “reconciled” if they are reconciled to and with the naturelessness of the four noble truths. They are to be called “reconciled” if they are reconciled to and with the naturelessness of the links of ignorant fabrication. They are to be called “reconciled” if they are reconciled to and with the naturelessness of all recognized phenomena, whether conditioned by ignorance or not. They are to be called “reconciled” if they are reconciled to and with naturelessness as inherent to everything they experience. Therefore, Sariputra, a commendable one who aspires to fully awaken, who thus proceeds in awakened understanding, is to be called “reconciled”.

Besides the five aspects of experience, another way the Buddhist tradition divides and breaks apart what we experience is the twelve sensory supports (ayatana). These include the eyes and the sights they perceive, the ears and the sounds they perceive, the nose and what it smells, the tongue and what it tastes, the body and what it feels, and the mind and what it conceives. If we add to these six pairs of sensory supports the corresponding consciousness (e.g., the auditory consciousness associated with the ears and with hearing), we have the eighteen elements or constituents of experience (dhatu), yet another way to divide up what is happening. However, like the five aspects of experience, we eventually realize that these lists are conceptual divisions that we project onto experience, and in the end they also have no inherent nature.

This principle is then extended to two well-known Buddhist formulations, namely the Four Noble Truths which describe the spiritual path and the Twelve Links of Conditioned Experience which describe how we “condition” what we experience by which we suffer. Though these lists can be very helpful in some ways, and it may seem as though they point to actual or real aspects of life, in the end they too are seen to be mental creations that have no inherent nature. And of course, since both lists describe how we suffer, awakening must make them redundant.

Finally, we must reconcile ourselves to the fact that naturelessness applies to everything we experience, whether we superimpose our mental conditioning onto it or not. It is one thing to accept that a given teaching or formulation is simply a means to an end and can eventually be left behind, and quite another to accept that everything we experience, including and especially the mind and body which comprise “us”, will also be seen to be natureless interpretations. To be told this and not recoil in fear is what a “commendable one who aspires to fully awaken” can and must do.

I note that if we were to take the final translated statement just above, and combine it with the naturelessness of the five aspects of experience as presented earlier, we would have something like:

This principle is then extended to two well-known Buddhist formulations, namely the Four Noble Truths which describe the spiritual path and the Twelve Links of Conditioned Experience which describe how we “condition” what we experience by which we suffer. Though these lists can be very helpful in some ways, and it may seem as though they point to actual or real aspects of life, in the end they too are seen to be mental creations that have no inherent nature. And of course, since both lists describe how we suffer, awakening must make them redundant.

Finally, we must reconcile ourselves to the fact that naturelessness applies to everything we experience, whether we superimpose our mental conditioning onto it or not. It is one thing to accept that a given teaching or formulation is simply a means to an end and can eventually be left behind, and quite another to accept that everything we experience, including and especially the mind and body which comprise “us”, will also be seen to be natureless interpretations. To be told this and not recoil in fear is what a “commendable one who aspires to fully awaken” can and must do.

I note that if we were to take the final translated statement just above, and combine it with the naturelessness of the five aspects of experience as presented earlier, we would have something like:

The commendable one who aspires to fully awaken, who proceeds in awakened understanding, understands that the five aspects of experience are natureless.

This is essentially the opening of the Heart Sutra. Jan Nattier concluded that the Heart Sutra was built around a specific passage found in the Large Sutra, with additional introductory and concluding material that have no parallel in the Larger Sutra. However, I suggest that the introductory section of the Heart Sutra was apparently taken from the Large Sutra as well.

As to the concluding portion of the Heart Sutra, which comes after the lines extracted from this section of the Large Sutra, its first several lines appear to correspond to passages just a bit later in the Large Sutra. Edward Conze translates these later passages as "dwelling in the perfection of wisdom, they will know full enlightenment... that Bodhisattva will meet with no impediments at all... the past, present and future Buddhas... coursing in just this (awakened understanding) have known full enlightenment". As a result, it may be that only the concluding mantra portion of the Heart Sutra was created by its Chinese authors, with everything prior to it being a paraphrase or direct quote from the Large Sutra.

As to the concluding portion of the Heart Sutra, which comes after the lines extracted from this section of the Large Sutra, its first several lines appear to correspond to passages just a bit later in the Large Sutra. Edward Conze translates these later passages as "dwelling in the perfection of wisdom, they will know full enlightenment... that Bodhisattva will meet with no impediments at all... the past, present and future Buddhas... coursing in just this (awakened understanding) have known full enlightenment". As a result, it may be that only the concluding mantra portion of the Heart Sutra was created by its Chinese authors, with everything prior to it being a paraphrase or direct quote from the Large Sutra.