The First Fetter

Self View

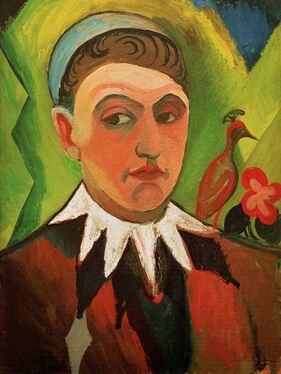

August Macke

August Macke

The first fetter is the most artificial, yet most convincing, illusion of all: that there is a separate “self” that we have or are, that goes by our name, and is the agent, controller or experiencer of all that is happening. If all the other nine fetters are in place - all of the subject/object dualities, the likes and dislikes, and everything else - all of that goes into the illusion of a separate and abiding “self” that has and in fact is all of those. For example, with the 6th fetter, by which it seems there is a “subject” (which all else is in relation to as an “object”), that “subject” is something we have, and in fact are.

If we were to look at the fetters in reverse, the process of believing in and assembling a “self” started at the 8th fetter with the intangible yet convincing belief that “I Exist”. How and why “I Exist” comes to fruition here as the 1st fetter, in that we essentially draw a dotted line around all those attributes and say “that’s me!” We become so committed to this separate “self” that we use everything in experience to continually prove and bolster it. Simply raising our right hand is assumed to be something that the self causes and does, with the hand also being something that the self owns and thus is.

As with all fetters, the view that there is a separate 'self" comes about because of the inborn tendency to do so. Here, our tendency is to conclude that someone has and indeed is all the various thoughts, reactions, and everything else that occurs in our experience. For example, having become convinced in the 7th fetter that “consciousness” is real, and that sensory experience via physical (and mental) spheres of consciousness is a valid perspective and explanation as to what is happening and why, we naturally assume there has to be someone behind it all, in charge of consciousness and directing it to what we are conscious of.

Seeing that there really is no “self” which directs and has our experience can be as simple as raising your right arm and looking for the “self” that made that happen. This is not a conceptual exercise, for example by reflecting on how there cannot be such a real self because everything is impermanent. Instead, we use our natural introspective ability to directly look, in simple, everyday experience, for the self that raised that arm, and who exactly raising our right arm apparently proves or attests to. Similarly, when a thought naturally arises, we can look for the “self” that gave rise to that thought, instead of simply assuming that “it was me!”. We might suppose there is such a "self", but we will never actually find one!

When we see this fact clearly, this fetter finally breaks, and the separate “self” is seen to have been nothing more than inference and interpretation. We then see how the truth has been right under our nose all along: there’s simply nobody (t)here! Because there never was a “self” in the first place, no longer believing that we have or are a separate “self” is not a destructive or negative experience: there is no ‘self’ that died, and there is no new ‘self’ that takes its place. In fact, for many if not most people, this is a very positive experience, in that we not only start to see what the Buddha was trying to teach us, but are also finally relieved of the burden of a “self” to which we always catered and which seemed to require an endless amount of time and energy to maintain.

This can also illustrate the need for caution as to how far we take the metaphor of self-growth, self-transformation and self-development, which may be initially helpful if we tend towards nihilism. These sorts of concepts can eventually hinder our ability to let go of the belief that there is a “self” that could grow or develop, in that we may believe there is an impermanent or changing “self” that could possibly do so, a belief that can be quite difficult to let go of.

As a point of comparison, in the Buddhist tradition, the path described by the first three Mahayana stages (bhumis), as a result of getting this first irreversible understanding of who we are(n’t), there is a joyfulness, an initial cleansing of wrong views, and an illumination of what is (and is not) happening within and around us. Though this illumination is of a preliminary nature, it nevertheless constitutes a significant re-ordering of how we perceive ourselves and our place in the world. In the Mahamudra yogas, this is the stage of one-pointedness, which I take to mean that we finally have a foothold in what the Dharma means, by which we can start to narrow our focus on what is most important and helpful, even if that means no longer engaging with certain practices or approaches that we were initially or naturally drawn to.

If we were to look at the fetters in reverse, the process of believing in and assembling a “self” started at the 8th fetter with the intangible yet convincing belief that “I Exist”. How and why “I Exist” comes to fruition here as the 1st fetter, in that we essentially draw a dotted line around all those attributes and say “that’s me!” We become so committed to this separate “self” that we use everything in experience to continually prove and bolster it. Simply raising our right hand is assumed to be something that the self causes and does, with the hand also being something that the self owns and thus is.

As with all fetters, the view that there is a separate 'self" comes about because of the inborn tendency to do so. Here, our tendency is to conclude that someone has and indeed is all the various thoughts, reactions, and everything else that occurs in our experience. For example, having become convinced in the 7th fetter that “consciousness” is real, and that sensory experience via physical (and mental) spheres of consciousness is a valid perspective and explanation as to what is happening and why, we naturally assume there has to be someone behind it all, in charge of consciousness and directing it to what we are conscious of.

Seeing that there really is no “self” which directs and has our experience can be as simple as raising your right arm and looking for the “self” that made that happen. This is not a conceptual exercise, for example by reflecting on how there cannot be such a real self because everything is impermanent. Instead, we use our natural introspective ability to directly look, in simple, everyday experience, for the self that raised that arm, and who exactly raising our right arm apparently proves or attests to. Similarly, when a thought naturally arises, we can look for the “self” that gave rise to that thought, instead of simply assuming that “it was me!”. We might suppose there is such a "self", but we will never actually find one!

When we see this fact clearly, this fetter finally breaks, and the separate “self” is seen to have been nothing more than inference and interpretation. We then see how the truth has been right under our nose all along: there’s simply nobody (t)here! Because there never was a “self” in the first place, no longer believing that we have or are a separate “self” is not a destructive or negative experience: there is no ‘self’ that died, and there is no new ‘self’ that takes its place. In fact, for many if not most people, this is a very positive experience, in that we not only start to see what the Buddha was trying to teach us, but are also finally relieved of the burden of a “self” to which we always catered and which seemed to require an endless amount of time and energy to maintain.

This can also illustrate the need for caution as to how far we take the metaphor of self-growth, self-transformation and self-development, which may be initially helpful if we tend towards nihilism. These sorts of concepts can eventually hinder our ability to let go of the belief that there is a “self” that could grow or develop, in that we may believe there is an impermanent or changing “self” that could possibly do so, a belief that can be quite difficult to let go of.

As a point of comparison, in the Buddhist tradition, the path described by the first three Mahayana stages (bhumis), as a result of getting this first irreversible understanding of who we are(n’t), there is a joyfulness, an initial cleansing of wrong views, and an illumination of what is (and is not) happening within and around us. Though this illumination is of a preliminary nature, it nevertheless constitutes a significant re-ordering of how we perceive ourselves and our place in the world. In the Mahamudra yogas, this is the stage of one-pointedness, which I take to mean that we finally have a foothold in what the Dharma means, by which we can start to narrow our focus on what is most important and helpful, even if that means no longer engaging with certain practices or approaches that we were initially or naturally drawn to.

Links