The Third Fetter

Attachment to Rites and Rituals

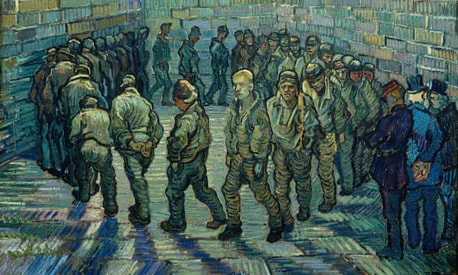

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh

The 3rd fetter describes how we identify with (and even as) our rites and rituals, whether they be of a day-to-day sort or (as it is typically seen as a “fetter”) the rites and rituals of our spiritual life. With desire and ill will as the 4th and 5th fetters in place, we come to have a definite view as to what we like and what we don’t like, such that we will naturally be drawn towards some things and repelled by others.

For example, we might gravitate towards certain spiritual practices and reject others, or on a more mundane level seize upon certain rituals in daily life as ostensible “proof” that we exist as we believe we do. Whatever the form it takes, it allows the inborn tendency for “this is what I do, and this is what I don’t do” to become a motive force in our lives. Though on the surface it may seem that we go through life only vaguely aware of what we do, those rites and rituals have a definite purpose: to support the notion of a separate and unique “self”.

The self-referent illusion here is that there is something we have that resonates with, or perhaps even is the storehouse for, what we do and don’t do, such as a particular ethical or religious observance, such that we become attached to it. It is as if something about us resonates and identifies with the rite or ritual, such that the activity benefits, defines and reinforces “who we are”. It is therefore natural to further conclude, with this as a basis, that there is a “self” which does all that, and is the controller, agent and experiencer of it all (i.e., as the first fetter).

Among other things, this fetter can lead us to pursue a path in which we seek to “find out who we really are”, rather than who we really aren’t. We might adopt the notion of “my spiritual practice”, in which we do what we are inclined to do which, rather than dismantling the illusion of a “self”, can tend to reinforce it. With desire and ill will in place, a particular rite or ritual might be something we really want to be happening, and which makes us feel good; practice becomes a matter of what we want to do, and pushing away what we don’t want to do.

The particular practice itself, such as meditating, study, visualization, or devotional practice, is of course not a problem per se: it’s that we attach to that practice and use it to bolster the sense of a separate self. We make it a problem, in other words. In doing so, we might even go so far as to say that the spiritual life must include meditation, devotional practice, study or another element because we can’t imagine not doing it. In more mundane terms, it might be that we insist on having our coffee or tea a certain way, and subconsciously use what is really just a preference as a way to reinforce our experience as being a separate and unique person.

Traditionally, when the 1st fetter falls, we realize that the rites and rituals we were attached to weren’t reinforcing anything (or anyone), such that the 3rd fetter falls as well. It might be said that we realize that there was never anyone who had been "doing" these things in the first place, thus the view that "I" can develop, have a spiritual practice or be discovered falls away. As with the 2nd fetter, focusing on how we grasp at rites and rituals, whether of a spiritual or mundane type, isn’t necessarily a primary focus of inquiry. Of course, observing how attached we are to the way in which spiritual progress ostensibly “must” occur can nevertheless be helpful and even necessary.

For example, we might gravitate towards certain spiritual practices and reject others, or on a more mundane level seize upon certain rituals in daily life as ostensible “proof” that we exist as we believe we do. Whatever the form it takes, it allows the inborn tendency for “this is what I do, and this is what I don’t do” to become a motive force in our lives. Though on the surface it may seem that we go through life only vaguely aware of what we do, those rites and rituals have a definite purpose: to support the notion of a separate and unique “self”.

The self-referent illusion here is that there is something we have that resonates with, or perhaps even is the storehouse for, what we do and don’t do, such as a particular ethical or religious observance, such that we become attached to it. It is as if something about us resonates and identifies with the rite or ritual, such that the activity benefits, defines and reinforces “who we are”. It is therefore natural to further conclude, with this as a basis, that there is a “self” which does all that, and is the controller, agent and experiencer of it all (i.e., as the first fetter).

Among other things, this fetter can lead us to pursue a path in which we seek to “find out who we really are”, rather than who we really aren’t. We might adopt the notion of “my spiritual practice”, in which we do what we are inclined to do which, rather than dismantling the illusion of a “self”, can tend to reinforce it. With desire and ill will in place, a particular rite or ritual might be something we really want to be happening, and which makes us feel good; practice becomes a matter of what we want to do, and pushing away what we don’t want to do.

The particular practice itself, such as meditating, study, visualization, or devotional practice, is of course not a problem per se: it’s that we attach to that practice and use it to bolster the sense of a separate self. We make it a problem, in other words. In doing so, we might even go so far as to say that the spiritual life must include meditation, devotional practice, study or another element because we can’t imagine not doing it. In more mundane terms, it might be that we insist on having our coffee or tea a certain way, and subconsciously use what is really just a preference as a way to reinforce our experience as being a separate and unique person.

Traditionally, when the 1st fetter falls, we realize that the rites and rituals we were attached to weren’t reinforcing anything (or anyone), such that the 3rd fetter falls as well. It might be said that we realize that there was never anyone who had been "doing" these things in the first place, thus the view that "I" can develop, have a spiritual practice or be discovered falls away. As with the 2nd fetter, focusing on how we grasp at rites and rituals, whether of a spiritual or mundane type, isn’t necessarily a primary focus of inquiry. Of course, observing how attached we are to the way in which spiritual progress ostensibly “must” occur can nevertheless be helpful and even necessary.

Links