Characteristics, or Reminders?

One of the primary teachings in Buddhism, particularly within the Pali tradition, is that of the three lakkhaṇa (Sanskrit lakṣaṇa). This is often translated as the three “characteristics” or “marks”, which are considered to be descriptors of all that exists. These characteristics or marks apply not just to ourselves but to everything else as well (including coffee cups) as “the way things really are”. This may give the impression that these three terms are not just universal in application to all that exists, but also that they are definitive, and that they offer an affirmative description of whatever is being described.

The customary interpretation of the three “characteristics” is that everything is impermanent (anicca), that nothing has a “self”, or essence (anattā), and that suffering is inherently part of life (dukkha). This is such a standard and familiar way of interpreting these three terms that we might take it for granted. However, though this may be the approach taken by many Buddhist traditions, it can serve to keep the practitioner in a world of dualistic concepts such as “impermanence” and the notion that they can (and should) come to a conceptual understanding of the nature of what is happening in and around them.

What can make this more conceptual approach so convincing is that it makes complete sense at the conventional level, in that we can easily project these three “characteristics” onto whatever it is we see, hear or think. For example, one can contemplate (i.e., think about) how composite things such as flowers and coffee cups are of a composite nature, are therefore impermanent and subject to decay and destruction. By this line of thinking, they cannot have an enduring essence, thus seeking lasting satisfaction from them is not possible. At the level of everyday convention, this is of course true of all that exists.

However, this assumes that “existence” accurately describes what we experience, by which everything has an affirmable and describable nature such as being “impermanent”. If one makes such an assumption, then spiritual practice will be a matter of trying to induce or realize a full experience of these three supposed truths by becoming more and more deeply convinced of them. Such a framework supports our natural tendency to want to understand and describe the world, be it coffee cups, flowers, or (especially) ourselves. However, while such knowledge and certainty might be what we want, it isn’t what happens when we awaken.

The customary interpretation of the three “characteristics” is that everything is impermanent (anicca), that nothing has a “self”, or essence (anattā), and that suffering is inherently part of life (dukkha). This is such a standard and familiar way of interpreting these three terms that we might take it for granted. However, though this may be the approach taken by many Buddhist traditions, it can serve to keep the practitioner in a world of dualistic concepts such as “impermanence” and the notion that they can (and should) come to a conceptual understanding of the nature of what is happening in and around them.

What can make this more conceptual approach so convincing is that it makes complete sense at the conventional level, in that we can easily project these three “characteristics” onto whatever it is we see, hear or think. For example, one can contemplate (i.e., think about) how composite things such as flowers and coffee cups are of a composite nature, are therefore impermanent and subject to decay and destruction. By this line of thinking, they cannot have an enduring essence, thus seeking lasting satisfaction from them is not possible. At the level of everyday convention, this is of course true of all that exists.

However, this assumes that “existence” accurately describes what we experience, by which everything has an affirmable and describable nature such as being “impermanent”. If one makes such an assumption, then spiritual practice will be a matter of trying to induce or realize a full experience of these three supposed truths by becoming more and more deeply convinced of them. Such a framework supports our natural tendency to want to understand and describe the world, be it coffee cups, flowers, or (especially) ourselves. However, while such knowledge and certainty might be what we want, it isn’t what happens when we awaken.

Image by Judith Scharnowski

Image by Judith Scharnowski

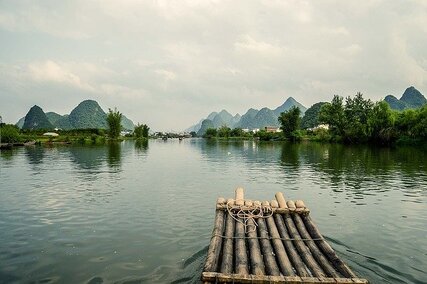

Holding On to the Raft

The Buddha is said to have described his teachings as being like a raft which we construct to cross a great expanse of water. The fact that we possess such a fine raft can lead to the tendency to want to keep it, and to hoist it over our shoulders and carry it around once we get across to our destination on the far shore. Instead, we are cautioned to let go of the raft, and leave it at the shore, by which we can freely move about once we reach that destination.

In the case of the three lakkhaṇa, the tendency to hold on to these portions of the raft can take the form of assuming that they not only help us to awaken, but also that their meaning will be something that we carry around with us once awake. If so, we will assume that they are the three basic basic facts of existence, in which case there will always be existing “things” to which those facts apply. For example, we will assume that we ourselves are impermanent, and that we have an “self” which changes, rather than seeing that we don’t exist in any way whatsoever. Further, if suffering is a fact of existence, then the cessation of suffering in this life is impossible, which invalidates the primary teaching of the Buddha that suffering can and does cease.

Also, seeing these three qualities as facts, or “the way things really are”, is based on the assumption that how we see things today (for example, as “impermanent”) will necessarily be the way we always see things. It thus presumes that our basic experience of the world won’t appreciably change, and that the properties we can see or at least understand today will always be so.

The desire to understand and describe what is happening is reflected in the two main areas of metaphysical philosophy, where ontology is the study of reality and epistemology is the study of knowledge. However, awakening involves neither of these. In the end, there is no “reality” or “knowledge” to study or know - it might be said that awakening is about overcoming the tendency to pursue one and/or the other of these two philosophical aspirations. Whatever we believe is real or that we know is really just an inference, or at best true only at the level of convention.

The Three Reminders

As we saw with the coffee cup earlier, the three lakkhaṇa are “characteristics” only in terms of the version of the coffee cup that we might have in our minds, rather than what we directly see. Thus, rather than “facts”, the lakkhaṇa as characteristics are inferences, and even speculations.

If the usual understanding of these three terms as characteristics or facts does not hold up, what might more appropriate translations for each term be? Looking at the original Pali and Sanskrit terms for each of the three reminders themselves, we see that they are cast in the negative. In other words, they remind us that what we believe to be the case really isn’t so. Therefore, rather than seeking to understand ‘the way things really are’, it is more a matter of understanding the way they are not.

It can be helpful to recognize that everything we experience is the result of sensory experience, which can provisionally be divided up into what we see, what we hear, what we think, and so on. While we are able to further interpret sensory experience and conclude (at least conventionally) that there is a world “out there” and a world “in here”, it is really just that: an interpretation. As the Buddha was recorded to have said in “The Teaching Regarding Everything” (The Sabba Sutta, SN 35.23):

The Buddha is said to have described his teachings as being like a raft which we construct to cross a great expanse of water. The fact that we possess such a fine raft can lead to the tendency to want to keep it, and to hoist it over our shoulders and carry it around once we get across to our destination on the far shore. Instead, we are cautioned to let go of the raft, and leave it at the shore, by which we can freely move about once we reach that destination.

In the case of the three lakkhaṇa, the tendency to hold on to these portions of the raft can take the form of assuming that they not only help us to awaken, but also that their meaning will be something that we carry around with us once awake. If so, we will assume that they are the three basic basic facts of existence, in which case there will always be existing “things” to which those facts apply. For example, we will assume that we ourselves are impermanent, and that we have an “self” which changes, rather than seeing that we don’t exist in any way whatsoever. Further, if suffering is a fact of existence, then the cessation of suffering in this life is impossible, which invalidates the primary teaching of the Buddha that suffering can and does cease.

Also, seeing these three qualities as facts, or “the way things really are”, is based on the assumption that how we see things today (for example, as “impermanent”) will necessarily be the way we always see things. It thus presumes that our basic experience of the world won’t appreciably change, and that the properties we can see or at least understand today will always be so.

The desire to understand and describe what is happening is reflected in the two main areas of metaphysical philosophy, where ontology is the study of reality and epistemology is the study of knowledge. However, awakening involves neither of these. In the end, there is no “reality” or “knowledge” to study or know - it might be said that awakening is about overcoming the tendency to pursue one and/or the other of these two philosophical aspirations. Whatever we believe is real or that we know is really just an inference, or at best true only at the level of convention.

The Three Reminders

As we saw with the coffee cup earlier, the three lakkhaṇa are “characteristics” only in terms of the version of the coffee cup that we might have in our minds, rather than what we directly see. Thus, rather than “facts”, the lakkhaṇa as characteristics are inferences, and even speculations.

If the usual understanding of these three terms as characteristics or facts does not hold up, what might more appropriate translations for each term be? Looking at the original Pali and Sanskrit terms for each of the three reminders themselves, we see that they are cast in the negative. In other words, they remind us that what we believe to be the case really isn’t so. Therefore, rather than seeking to understand ‘the way things really are’, it is more a matter of understanding the way they are not.

It can be helpful to recognize that everything we experience is the result of sensory experience, which can provisionally be divided up into what we see, what we hear, what we think, and so on. While we are able to further interpret sensory experience and conclude (at least conventionally) that there is a world “out there” and a world “in here”, it is really just that: an interpretation. As the Buddha was recorded to have said in “The Teaching Regarding Everything” (The Sabba Sutta, SN 35.23):

Monks, what is it that I call “everything”? It is the eye and forms, the ear and sounds, the nose and odors, the tongue and tastes, the body and what is contacted, the mind and mental phenomena. That’s it: that’s everything. If someone should say that “I know or can point to something else besides all that is perceptible to the senses”, they are saying that there is another, more desirable reality. And yet, if asked about this statement, they could not elaborate, and they would become upset. And why? This supposed “other reality” is not something they can actually perceive.

For example, we come to assume that we have or perceive an “inner” world, therefore an “outer” world as well. However, do we actually perceive two such worlds? However, as you look at these words right now, can you actually see, to within a quarter of an inch, where the boundary of an inner world ends and an outer world begins? Or, is the sense of an inner and outer world only an interpretation of what is simply seen? If you resort to thinking about it, you might suppose that the boundary of your inner visual world is at the surface of the eye, but can you actually see such a boundary?

If everything is simply the content of our experience, anything we remind ourselves of only concerns us and what we believe is happening in our experience. Rather than being facts about the world around us, the lakkhaṇa are reminders that we don’t know what we think we know about experience. Specifically, as described in subsequent sections, they can remind us that (1) there is nothing that was ever internal to us, (2) there is no “me” in experience, and (3) things don’t always go as we prefer.

We Aren’t What We Think We Are

If understood as reminders, these three terms don’t say anything definitive about the nature of what we see, hear or think; rather, they are reminders that we cannot own, identify with or place expectations or conditions upon anything we experience. They don’t affirmatively describe what is happening “out there”, but simply clarify that who or what we assume is “in here” isn’t actually so. The three reminders are universal, but only in the sense that we all tend to adopt certain erroneous beliefs about ourselves, therefore all of us need to eventually drop those beliefs if we are to awaken. And once awake, we will no longer need reminding - the three reminders will have done their job, and will no longer have any particular benefit.

As the Buddha is recorded to have said in “The Teaching on What Appears” (The Uppāda Sutta, AN 3.136), that the three reminders are needed because we create in our mind a version of what we experience that is or could be internal, always pleasing, and something that is or is part of our identity (i.e., “me”). In other words, out of ignorance, we condition ourselves to believe that those three descriptors can and in fact do hold true. The Buddha therefore stated, in summary:

If everything is simply the content of our experience, anything we remind ourselves of only concerns us and what we believe is happening in our experience. Rather than being facts about the world around us, the lakkhaṇa are reminders that we don’t know what we think we know about experience. Specifically, as described in subsequent sections, they can remind us that (1) there is nothing that was ever internal to us, (2) there is no “me” in experience, and (3) things don’t always go as we prefer.

We Aren’t What We Think We Are

If understood as reminders, these three terms don’t say anything definitive about the nature of what we see, hear or think; rather, they are reminders that we cannot own, identify with or place expectations or conditions upon anything we experience. They don’t affirmatively describe what is happening “out there”, but simply clarify that who or what we assume is “in here” isn’t actually so. The three reminders are universal, but only in the sense that we all tend to adopt certain erroneous beliefs about ourselves, therefore all of us need to eventually drop those beliefs if we are to awaken. And once awake, we will no longer need reminding - the three reminders will have done their job, and will no longer have any particular benefit.

As the Buddha is recorded to have said in “The Teaching on What Appears” (The Uppāda Sutta, AN 3.136), that the three reminders are needed because we create in our mind a version of what we experience that is or could be internal, always pleasing, and something that is or is part of our identity (i.e., “me”). In other words, out of ignorance, we condition ourselves to believe that those three descriptors can and in fact do hold true. The Buddha therefore stated, in summary:

Monks, whether or not an awakened one arises, the following is true:

- whatever you mentally condition to be internal to you is not;

- whatever you mentally condition to always go as you prefer does not;

- none of the phenomena you experience, whether mentally conditioned or not, are “me”.

By this, once we awaken and suffering ceases, we have stopped conditioning ourselves to believe or expect that anything could be internal to us or always go as we might want. And yet, we will still experience phenomena such as “coffee cups” in daily life, just as we always have. However, we will no longer condition ourselves to assume that anything related to the coffee cup, such as the seeing of the cup or the smelling the coffee inside, proves or is connected to any sort of “me” or “I”.