The Reminder that Things Don’t Always Go As We Prefer

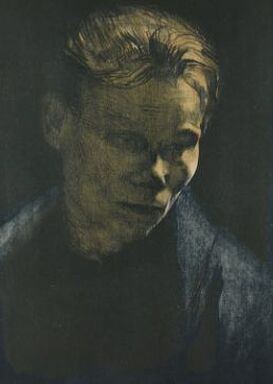

Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Kollwitz

The reminder of dukkha tells us that, at times (or perhaps fairly often), life doesn’t go as we might prefer; as a result, we will not feel as we might prefer either, experiencing discomfort, unpleasantness and even pain. Our tendency, though, is to assume that, if we don’t feel good or are not comfortable, and there is a mismatch between what we prefer and what we actually experience, what is happening is unacceptable and even wrong.

In other words, we resist what is happening, due to how we basically feel about it, by which we experience the anguish and distress of suffering. As with the other reminders, that we suffer if we resist how we fundamentally feel is entirely experiential: no words or concepts are necessary to know if there is resistance to what is happening, and if discomfort has led to suffering.

In ancient India, where animal-drawn carts were quite common, the word dukkha (which is composed of the terms for “bad” and “hole or aperture”) meant having a poor axle hole on a cart, which of course would lead to an uncomfortable journey in the cart. In the West, we might say that “life can be a bumpy ride”, which says essentially the same thing. However, whether it is a bumpy ride in a cart or hearing some unwelcome news, does there have to also be the anguish and distress of suffering, simply because there is a mismatch between what we want and what we get?

First and Second Darts

One way the Buddhist tradition discusses this perceived mismatch is in terms of first and second darts. As the Buddha is recorded to have said in the Dart Sutta, when those who are not awake experience an uncomfortable physical sensation in the body, they worry and grieve, they lament, beat their breast, weep and are distraught. Such unpleasant or uncomfortable sensations can arise due to a physical cause (e.g., stubbing their toe), or perhaps more commonly from a mental event such as being criticized or seeing something disturbing: whatever the source, these initial sensations cannot be avoided, even though we might prefer otherwise.

However, if one expects that they could or should be able to avoid all unpleasantness whatsoever, and therefore resists how they feel at a fundamental physical level, one experiences a second wave of sensations, in addition to the initial bodily feeling. Put another way, whatever happens, if it doesn’t give rise to any discomfort, we are indifferent to it. For example, soybean prices in the United States generally declined between 2012 and 2019, before rebounding in mid-2020; while there are those for whom that is a significant fact, the rest of us may not feel one way or the other about it because we have no appreciable response to it.

Of course, there are many people and issues in our life that are much more significant to us, and which give rise to discomfort. Due to resisting that initial feeling there arises a second or subsequent set of feelings, one that leads to even more resistance and an even more unpleasant physical feeling. For example, if someone insults us, some very visceral sensation in our stomach, throat or arms can instantly arise, which we’ve come to associate with the onset of anger or frustration, which then manifest. As the Dart Sutta describes, it is as if someone were pierced by a first dart and, following that first piercing, they are hit by a self-inflicted second dart which produces even more unpleasant or uncomfortable physical feelings. This can continue on indefinitely - one might even talk in terms of third and fourth darts that arise as one builds up what was a bit of discomfort into an excruciating and unbearable situation, a swirl of thoughts and reactions that may have only taken a few seconds to produce but can take much longer to resolve.

That we tend to react to discomfort with anguish and distress is reflected in how English dictionaries typically define or illustrate the term “uncomfortable”. The synonyms include such terms as comfortless, distressing, unbearable, harsh, miserable, nasty, agonizing, excruciating, and even torturous… all equated with simply being uncomfortable(!). This sort of ambiguity also occurs with the word “feeling” in English, which can be used for both first darts (e.g., “I feel an uncomfortable sensation”) and for second darts (“I feel angry”). This is also reflected in definitions given in Pali and Sanskrit dictionaries for the corresponding word vedana, which can mean simply feeling or sensation, as well as pain, torture, or agony - it too is a potentially confusing and even misleading word as it is commonly used and understood.

Expectations: Could versus Should

That we tend to have such broad connotations for terms such as “discomfort” and “feeling” illustrates the importance of recognizing that while things always could be different for us, we can quickly assume and conclude that they should be different, and even must be different. This natural progression from “could” to “should”, and then from “should” to “must”, is essentially why we suffer: we cannot accept that life, and particularly how we basically feel about it, isn’t always as we might prefer it to be.

In other words, it’s not just that life doesn’t go as we might prefer: it also doesn’t go as we expect. And in particular, we might want to always feel good, but we cannot expect to always do so. What this reminder tells us is that unpleasant or uncomfortable physical sensations will indeed arise, should we hear some bad news or hit our thumb with a hammer. There is nothing right or wrong with this discomfort - it is simply what happens in the course of daily life.

A conceptual understanding of this reminder might be that, as long as there is attachment to things that are unstable, unreliable, changing and impermanent, there will be suffering. However, it doesn’t matter whether we are attached or unattached to things that (at the conventional level) are permanent or impermanent: discomfort nonetheless arises in life, and it is how we respond to that discomfort that is the issue. The arising of suffering is therefore not directly connected to “impermanence”.

This reminder is sometimes translated as “life is suffering”, which can give the misleading impression that suffering is potentially arising in every moment, or that all that we experience will inevitably lead to suffering, even once fully awake. It might also be understood to mean that, once awake, we will no longer feel discomfort at all, by which dukkha (as both first and second darts) will finally have ceased. Rather than either of those extremes being true, this reminder simply says that discomfort can and does arise: life doesn’t always turn out as we would prefer.

Letting Go of Expectations

A very useful traditional teaching is that there can be a “gap” between the initial sensations of discomfort that unavoidably arise and any reactions that might start to arise. In terms of the fetters approach, what we presume bridges this gap is the so-called “desire and ill will” that we believe is innate to our very existence and which compels the push and pull of reactivity. If we look directly, there is nothing that we have or are that makes such reactions necessary, by which we so routinely suffer. If we can stay with just the first dart, and in that “gap”, the apparent link between what is happening and reacting is broken, because we can directly see that there actually is no such link.

Initially, working within this “gap” is in terms of what is happening around us: what it is that other people and things are doing or not doing. However, that is merely the tip of the iceberg, in terms of how we suffer and why. Once past “desire and ill will”, the fetters that remain concern how and why we believe that we are entitled to feel a certain way, regardless of what might be happening.

Working with the last two fetters unearths the underlying tendency towards thinking that what is happening “should” be any different than it currently is, including how we basically feel about it. Even without any sense of “me”, suffering still arises as long as any unrealistic expectations persist. These final steps are the culmination of seeing more and more clearly that there isn’t anything or anyone that necessarily or inherently gives rise to “second darts”. Rather, it is just that life is not always comfortable - first darts simply arise - and that it is our unrealistic expectations around life always being comfortable that are the issue.

Eventually, we no longer have to be reminded that resistance to discomfort is futile - the reminder has done its job and can be set aside when suffering stops. Were one to instead assume, as some do, that this reminder is in fact “all things lead to suffering” or similar, and that we will always be liable to suffering unless we are in a certain “state” where we are temporarily immune to suffering, this would effectively invalidate the entire Buddhist path which teaches that suffering does in fact come to an end.

Just as no words or concepts are needed in order to know if first or second darts are present, it is entirely experiential when all second darts cease to arise. It is indeed quite obvious that suffering has ceased, since even in the most difficult of circumstances, the familiar resistance that once reliably arose is simply gone. This is so obvious that we know that the spiritual path is complete; as the Buddha so often said, at that point “birth is ended, the holy life fulfilled, the task done, and life is forever changed”. Again, it is not that discomfort stops happening, but rather that suffering is no longer our response to discomfort.

In the language of conditionality, we have finally de-conditioned our experience. Even words like “unsatisfactory” no longer apply, since we no longer wish or need to be “satisfied” with what is happening. While preferences in food, company, entertainment and the rest remain once fully awake, the fact that those preferences are not always met is no longer the occasion for the anguish and distress of suffering. The reminder that what happens in life won’t necessarily be to our liking is therefore no longer needed, because while what is happening could be otherwise, we no longer believe it should be otherwise.