The Sixth Fetter

The Illusion of Subjectivity

Image by i.pinimg

Image by i.pinimg

Why do we believe we have a unique perspective on what is happening?

The 6th fetter is the belief that we live in, and in fact are in the central position in, a world of objective forms (in the Pali language, rupa) that inherently possess the boundaries and separation that they appear to have. That appearance is founded upon the mistaken belief that everything doesn’t just exist, but exists in relationship to us. The experience of this relationship is that we are the “subject”, and all else are “objects". Once the previous fetters of desire and ill will are gone, we no longer insist that people and things around must be a certain way to suit our preferences and needs. However, we continue to insist that all of it must be as we currently perceive it: as a constellation of objects that revolve around us and are inherently separate from us.

The traditional term for this fetter literally translates as “insistence on form”. Here, form is not just in the sense of things having certain shapes or configurations, but the insistence that they are objects which are as tangible and distinct as they appear from our perspective. While ‘form’ is sometimes seen as being limited to physical forms such as trees and tables, it is also thoughts and ideas - anything carved out from experience and seen as having a separate existence. By this, nothing of significance in our lives is just any old thing: it is THAT thing, which exists as it appears because of our relationship to it.

For example, a mobile phone can just be an electronic device that everyone has, unless of course it is our phone, a particular phone that we have a relationship to and has a place in our lives. In other words, anything that is a part of our lives takes on a certain objective form, and has a certain meaning based on our subjective relationship to and with it. We don’t simply perceive the physical aspect of something or someone: there is also an aspect of how we feel about and otherwise experience it. By this, our identity is also as tangible and distinct as we believe it is: with this fetter in place, reacting in a push-pull way to what else is happening (i.e., the fetters of desire and ill will) is then justified.

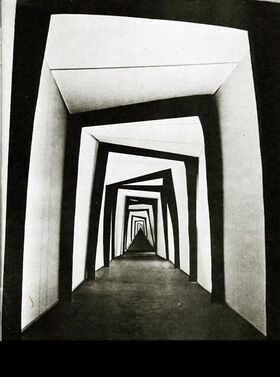

Because everything seemingly exists in relationship to us, the form we take is as the “subject”, the central and most important form, which is the reference point from which we perceive everything else as an "object". From that perspective, everything else, even our thoughts, comprise a world of objects that literally revolves around us: simply sweeping our head and thus our gaze from left to right can show how all visual information seems to funnel towards us. Even though we may know that everyone else also experiences the world in this way, in which they too see themselves as the central reference point, this perspective is so convincing that we take it as a given.

This fetter is sometimes presumed to mean that we become attached to certain meditation states associated with form (i.e., the rupa-jhanas). While these states can indeed be delightful and a bit habit-forming, they are what naturally happens when we temporarily relax our subjective perspective on the world. While becoming attached to these pleasant temporary states can obviously be an issue, the actual fetter or belief is that there is a world in which the ‘form’ we take is as the central subject, surrounded by a world of objects that have that sort of relationship to us: meditation simply gives us a temporary reprieve from this perspective. In other words, the fact that we can enter these temporary meditative "states" is a symptom of this underlying belief.

From an inquiry perspective, the self-referent belief is that there is something internal to us which corresponds to the label "subject", which we use as a reference point for all we perceive. If we observe closely, we can see that we regularly shuttle back and forth between what is happening in the world on the one hand, and to a certain location (often in the chest or throat area) to check in with this reference point as to what we think and feel about what is happening on the other. This isn’t to say that we shouldn’t be aware of our thoughts and feelings; rather, it is the habitual and even obsessive way in which we do that shuttling back and forth, by which that point to which we refer becomes a seemingly necessary reference point in our lives. By regularly doing this, at a very early age we become convinced that we are the central and most important thing/person in the world.

As a result of unconsciously and even compulsively “checking in” with what we think and feel about something or someone, it isn’t just any old something or someone that is is seen, heard or thought: it becomes THAT thing or person, which further affirms that we are THIS thing or person. This creates the subject/object duality that pervades our experience of life, as well as the appearance of the rigid boundaries that such a duality requires.

In exploring the 6th fetter, we therefore question whether there is such a reference point, our subjective pole as it were, by which we habitually contrast ourselves to the rest of the universe in a subject/object way. This stage of inquiry can therefore be rather uncomfortable at times, since we came to believe in our place as a subject not long after we were born. It may not occur to us that there is any other possible way of observing what is happening. And yet, if we follow where our attention goes if we attempt to refer to this point of reference, do we find anything?

Once this illusion falls, we no longer see ourselves as living in a world of forms, whether ourselves as the subject or anything else as an object. Boundaries are still perceived, but not to the extent that those boundaries seem to rigidly separate everything from “me”. Since what is perceived is no longer split into a subject and its objects, everything happening (including “me”) will now have the same precedence. If life were a play, instead of being the central player or star of the show, we are now just one actor among many on the stage. While there is still a tangible sense of “me” or “I” (the focus of the 8th fetter), we see how life really doesn’t revolve around “me”. This shift allows us to start to see through the supposed separation between self and others, and decreases the degree to which we believe we are confined to the boundaries of mind and body. These and all other things seem to exist, but everything is now on an equal footing.

As with all fetters, rather than the experience of this shift being one of destruction or otherwise negative, it is typically quite positive, in that the mental and physical freedom we have always sought starts to manifest. It may be intuitive that if we start to loosen the supposed limitations of mind and body we have “subjected” ourselves to, it cannot but be a quite positive and even fascinating experience. Of all the shifts that occur when working with the fetters, the shift associated with the 6th fetter can be the least surprising or life-changing, in that it can be so obvious that the presumed subject/object duality was never actually there.

Breaking this fetter means that the outward appearance of things, and thus the way in which we have always seen them, irreversibly changes. However, it doesn’t mean there isn’t a “book over on the table” in conventional terms; it’s just that what a “book” or “table” is or means starts to change. The sense of there being absolute boundaries in what we perceive is no longer as strong: it might seem as though boundaries have softened, do not hold up, or at times may appear to have vanished altogether.

This shift can also lend a comparatively two-dimensional appearance to what is perceived, because our exaggerated sense of depth is relaxed. We no longer see ourselves as being as separate from all else, and yet depth perception as we’ve come to know it persists by which we can still drive a car and get across the street. It might be said that there is a more natural sense of three-dimensional perception, which binocular vision (that results from having two horizontally-separated eyes) inherently provides, though it can take a little time before this more subtle 3-D perspective becomes the “new normal”.

In terms of the other path descriptions in the Buddhist tradition, this shift corresponds to the sixth Mahayana stage (bhumi) of “turning toward”, and coming “face to face” with what is actually happening. Though we haven’t yet dispelled all delusions about the nature of what we perceive, we are starting to get a much clearer picture of what is (and isn’t) actually happening, because we are in a position to examine it directly. In the Mahamudra tradition, this step corresponds to the initial stage of the yoga of the “one taste of emptiness”, where we start to see that lived experience is empty of the mentally-fabricated versions of what we perceive.

The 6th fetter is the belief that we live in, and in fact are in the central position in, a world of objective forms (in the Pali language, rupa) that inherently possess the boundaries and separation that they appear to have. That appearance is founded upon the mistaken belief that everything doesn’t just exist, but exists in relationship to us. The experience of this relationship is that we are the “subject”, and all else are “objects". Once the previous fetters of desire and ill will are gone, we no longer insist that people and things around must be a certain way to suit our preferences and needs. However, we continue to insist that all of it must be as we currently perceive it: as a constellation of objects that revolve around us and are inherently separate from us.

The traditional term for this fetter literally translates as “insistence on form”. Here, form is not just in the sense of things having certain shapes or configurations, but the insistence that they are objects which are as tangible and distinct as they appear from our perspective. While ‘form’ is sometimes seen as being limited to physical forms such as trees and tables, it is also thoughts and ideas - anything carved out from experience and seen as having a separate existence. By this, nothing of significance in our lives is just any old thing: it is THAT thing, which exists as it appears because of our relationship to it.

For example, a mobile phone can just be an electronic device that everyone has, unless of course it is our phone, a particular phone that we have a relationship to and has a place in our lives. In other words, anything that is a part of our lives takes on a certain objective form, and has a certain meaning based on our subjective relationship to and with it. We don’t simply perceive the physical aspect of something or someone: there is also an aspect of how we feel about and otherwise experience it. By this, our identity is also as tangible and distinct as we believe it is: with this fetter in place, reacting in a push-pull way to what else is happening (i.e., the fetters of desire and ill will) is then justified.

Because everything seemingly exists in relationship to us, the form we take is as the “subject”, the central and most important form, which is the reference point from which we perceive everything else as an "object". From that perspective, everything else, even our thoughts, comprise a world of objects that literally revolves around us: simply sweeping our head and thus our gaze from left to right can show how all visual information seems to funnel towards us. Even though we may know that everyone else also experiences the world in this way, in which they too see themselves as the central reference point, this perspective is so convincing that we take it as a given.

This fetter is sometimes presumed to mean that we become attached to certain meditation states associated with form (i.e., the rupa-jhanas). While these states can indeed be delightful and a bit habit-forming, they are what naturally happens when we temporarily relax our subjective perspective on the world. While becoming attached to these pleasant temporary states can obviously be an issue, the actual fetter or belief is that there is a world in which the ‘form’ we take is as the central subject, surrounded by a world of objects that have that sort of relationship to us: meditation simply gives us a temporary reprieve from this perspective. In other words, the fact that we can enter these temporary meditative "states" is a symptom of this underlying belief.

From an inquiry perspective, the self-referent belief is that there is something internal to us which corresponds to the label "subject", which we use as a reference point for all we perceive. If we observe closely, we can see that we regularly shuttle back and forth between what is happening in the world on the one hand, and to a certain location (often in the chest or throat area) to check in with this reference point as to what we think and feel about what is happening on the other. This isn’t to say that we shouldn’t be aware of our thoughts and feelings; rather, it is the habitual and even obsessive way in which we do that shuttling back and forth, by which that point to which we refer becomes a seemingly necessary reference point in our lives. By regularly doing this, at a very early age we become convinced that we are the central and most important thing/person in the world.

As a result of unconsciously and even compulsively “checking in” with what we think and feel about something or someone, it isn’t just any old something or someone that is is seen, heard or thought: it becomes THAT thing or person, which further affirms that we are THIS thing or person. This creates the subject/object duality that pervades our experience of life, as well as the appearance of the rigid boundaries that such a duality requires.

In exploring the 6th fetter, we therefore question whether there is such a reference point, our subjective pole as it were, by which we habitually contrast ourselves to the rest of the universe in a subject/object way. This stage of inquiry can therefore be rather uncomfortable at times, since we came to believe in our place as a subject not long after we were born. It may not occur to us that there is any other possible way of observing what is happening. And yet, if we follow where our attention goes if we attempt to refer to this point of reference, do we find anything?

Once this illusion falls, we no longer see ourselves as living in a world of forms, whether ourselves as the subject or anything else as an object. Boundaries are still perceived, but not to the extent that those boundaries seem to rigidly separate everything from “me”. Since what is perceived is no longer split into a subject and its objects, everything happening (including “me”) will now have the same precedence. If life were a play, instead of being the central player or star of the show, we are now just one actor among many on the stage. While there is still a tangible sense of “me” or “I” (the focus of the 8th fetter), we see how life really doesn’t revolve around “me”. This shift allows us to start to see through the supposed separation between self and others, and decreases the degree to which we believe we are confined to the boundaries of mind and body. These and all other things seem to exist, but everything is now on an equal footing.

As with all fetters, rather than the experience of this shift being one of destruction or otherwise negative, it is typically quite positive, in that the mental and physical freedom we have always sought starts to manifest. It may be intuitive that if we start to loosen the supposed limitations of mind and body we have “subjected” ourselves to, it cannot but be a quite positive and even fascinating experience. Of all the shifts that occur when working with the fetters, the shift associated with the 6th fetter can be the least surprising or life-changing, in that it can be so obvious that the presumed subject/object duality was never actually there.

Breaking this fetter means that the outward appearance of things, and thus the way in which we have always seen them, irreversibly changes. However, it doesn’t mean there isn’t a “book over on the table” in conventional terms; it’s just that what a “book” or “table” is or means starts to change. The sense of there being absolute boundaries in what we perceive is no longer as strong: it might seem as though boundaries have softened, do not hold up, or at times may appear to have vanished altogether.

This shift can also lend a comparatively two-dimensional appearance to what is perceived, because our exaggerated sense of depth is relaxed. We no longer see ourselves as being as separate from all else, and yet depth perception as we’ve come to know it persists by which we can still drive a car and get across the street. It might be said that there is a more natural sense of three-dimensional perception, which binocular vision (that results from having two horizontally-separated eyes) inherently provides, though it can take a little time before this more subtle 3-D perspective becomes the “new normal”.

In terms of the other path descriptions in the Buddhist tradition, this shift corresponds to the sixth Mahayana stage (bhumi) of “turning toward”, and coming “face to face” with what is actually happening. Though we haven’t yet dispelled all delusions about the nature of what we perceive, we are starting to get a much clearer picture of what is (and isn’t) actually happening, because we are in a position to examine it directly. In the Mahamudra tradition, this step corresponds to the initial stage of the yoga of the “one taste of emptiness”, where we start to see that lived experience is empty of the mentally-fabricated versions of what we perceive.

Links